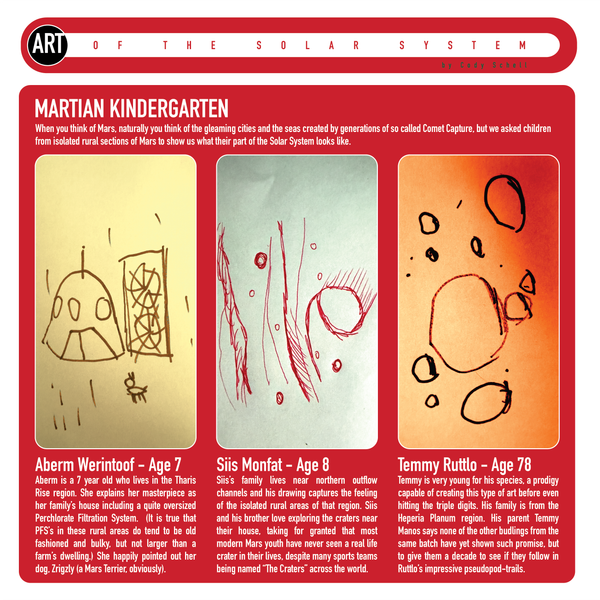

A Personal History of Horror Films in 101 Quirky Objects #81: The Doorbell in Repulsion (1974)

by Vince Stadon

“There's no need to be alone, you know. Poor little girl. All by herself. All shaking like a little frightened animal.” – Landlord

When that doorbell rings, Carol curls up into a ball, retreating into her internal space. The doorbell is the sound of intrusion into her world. It is the sound of men wanting to come into the apartment, into her bedroom, into her bed, climbing on top of her and pinning her down.

Carol’s inner space is difficult to understand. I’ve read reviews that pin Carol down as a paranoid schizophrenic, and other reviews say that Carol suffers from androphobia—extreme anxiety or fear of men, and both diagnoses feel to me to be too pat, too tidy. Catherine Deneuve plays Carol as almost childlike, sullen, shy, reserved. She picks at food, plays with her hair, softly sings to herself. But she is in the body of one of the world’s most beautiful women, and every man wants her, lusts after her, intrudes upon her.

Repulsion is set in a posh bit of London in 1965, possibly the most fashionable place on Earth at that time, and Carol looks like she absolutely belongs to this time and this place—until you properly look at her, at what’s going on with her, and then you realise that she is out of place everywhere except in her own internal space, where the doorbell never rings. With her little ticks and catatonic stare, her forgetfulness, her nightmares, and her need to keep the world away from her, Carol is a convincing depiction of someone with post-traumatic stress disorder. Repulsion never explains what has happened to Carol, but hints at childhood sexual abuse from her father. The only backstory we get is that Carol and her sister Helen are Belgian, and that they now live together in Helen’s rented apartment in South Kensington. Helen is the elder, capable, confident sister, handling all the (overdue) rent money and having an affair with a married man who takes her on a holiday to Tuscany, leaving Carol all alone with the rent money and the telephone and the doorbell. There’s also a skinned rabbit and potatoes for food. As Carol’s mental health deteriorates, the telephone rings louder (though there’s nobody there when she answers, except one time when a woman calls her a “stupid bitch”), the doorbell never stops ringing, and the food decomposes in the summer heat.

Who are these men ringing that bell? There’s Colin, who is attractive and aimable and looks so of the time and place that he might have stepped out of A Hard Day’s Night (1964), where he would have been photographed by Gilbert Taylor, Repulsion’s cinematographer. Colin is so obsessed with Carol that he literally breaks down her door to get to see her. When Carol kills him by bashing his brains out with a heavy candlestick, it almost feels like an act of exasperation. In the moment, we don’t sympathise with Colin, we are entirely with Carol.

The Landlord, a sleazy opportunist, has come for the rent money, but he sticks around once he’s pocketed it because Carol looks like Catherine Deneuve sweating in a flimsy nighty and he can’t help himself. Carol’s attack on him is much more frenzied and bloodier, slashing at him repeatedly with a cutthroat razor (left there by her sister’s boyfriend, much to Carol’s disgust), not through malice but with the intention of just simply making him stop, making him go away. Once he’s dead, Carol tips the sofa on top of him to hide him away so she can think no more about him.

Lastly, there is Michael, Helen’s lover, who returns during a downpour with Helen, and who has already stated that he believes Carol hates him. As Helen finds the bodies, Michael finds a catatonic Carol hiding under a bed, and he carries her out of the apartment with an enigmatic creepy smile on his face. Maybe he wants her out of the way. Maybe he wants her sexually. That smile could mean a lot of things. He is a man, and he has her in his arms.

By the end of Repulsion, the walls and the ceiling have closed in on Carol as her life has become a living nightmare. Every sound, every smell, everything in the world assaults her. The cracks in the walls are getting bigger. The walls themselves pulsate like clay. Suddenly and violently, the grasping arms of men burst through the walls, and they grope Carol and pull her hair. Outside isn’t any better. Carol works in the beauty industry because women are expected to be beautiful for men. The men who look at her and want to ring that doorbell.

Repulsion was made by Roman Polanski, who would rape a child. It was financed by men who made pornographic films—they were the only money men who would back the film, thinking it would be a profitable horror film. Celebrated on its release, Repulsion half-sank into obscurity (though it had many champions) until undergoing a renaissance during the #MeToo movement, when women all around the world spoke up about the sound of that doorbell ringing.

More obvious picks for an object to represent this film: the telephone; the skinned rabbit; the shaving brush; the razor; the bowl of sugar cubes; the tweezers; the candlestick holder; the rotting potatoes; the family photo

Repulsion (1965); 105 mins; UK

Directed by Roman Polanski; Written by Roman Polanski, Gérard Brach, David Stone; Produced by Gene Gutowski; Cinematography by Gilbert Taylor; Music by Chico Hamilton

Catherine Deneuve (Carol Ledoux); Ian Hendry (Michael); John Fraser (Colin); Yvonne Furneaux (Helen Ledoux); Patrick Wymark (Landlord); Renée Houston (Miss Balk); Valerie Taylor (Madame Denise); James Villiers (John); Helen Fraser (Bridget); Hugh Futcher (Reggie)