The Other Side of Empty

by Aeryn Rudel

Art by Arnold T. Blumberg

There’s a hole in me. I’m not speaking metaphorically. If I lift my shirt, you’ll see a black disk about the size of a softball just above my belly button. It doesn’t hurt, but it makes a strange noise, a low moaning, like wind through a tunnel.

The other night, I was sitting on the couch by myself—that’s not unusual; it’s hard to get close to people when you have a gaping void in the center of your body—and something pushed against my shirt, tenting it out. Then an object fell onto my lap. It was a stone, a perfectly smooth piece of speckled granite, like the kind you find in a riverbed. Someone on the other side had pushed it through me.

I stood up, terrified. I’d had the hole since I was a teenager, and no one knew about it. Nothing had ever come through before, and I’d never tried to put anything into it. The rock was warm in my hand, like it had been sitting in the sun or someone had been holding it.

That warmth awakened a desperate feeling in me, a need to communicate with whatever or whoever was on the other end. I raced to the kitchen, yanked open the junk drawer, and dug around until I found a Sharpie. I stood staring at the rock, trying to think of something to say. In the end, I just wrote HELLO? on the stone, lifted my shirt, and pushed it into the hole. The stone disappeared with a faint popping noise. I stood and waited under the fluorescent lights of my kitchen, holding my shirt hem under my chin. An hour passed, and nothing came back.

Finally, I let my shirt down and went to bed.

I fell asleep on my stomach. That’s how I usually sleep because I feel safer with the hole covered. When I woke up the next morning, I rolled over, and there on the bed was the stone. I snatched it up, grinning at its warmth, and I saw the simple message I’d written on one side. But on the other side, written in red ink, was a series of Chinese characters.

Excited and a little scared, I rushed to my computer and started looking at Hanzi characters online, but there were tens of thousands of them. Finally, I had to resort to taking a picture of the characters and asking someone I knew on a video game forum to translate. My forum buddy, BeijingBob74, sent back a laughing emoji and the translation: Do you have a hole too?

I sat back in my chair, one hand on my shirt, over the void in my body. I began to tremble; then came tears. There was someone out there like me, someone with a part of themselves cored out and missing.

There wasn’t any more room on the stone to write, so I grabbed a pad of Post-it notes off my desk. On the top one, I wrote: Yes. My name is Casey. What’s your name? Then I pulled up my shirt and pushed the whole pad through.

I didn’t have to wait long. About ten minutes later, the pad came back. My note had been removed and written on the next one, in English, was Chu Hua. I rushed to my computer and put the name into Google translate.

The name meant "chrysanthemum".

Over the next few weeks, Chu Hua and I went through dozens of Post-it pads. Passing them back and forth through each other. At first, we just gathered information. Where do you live? How old are you? How long have you had the hole? Does anyone know about it? We lived on opposite sides of the world, but our lives turned out to be painfully similar. Lonely. Held apart.

The messages began to change as we learned more about each other. We sent jokes (mostly about how Google translate butchered our respective languages). Little drawings. Gifts of sweets and other tiny things. Our connection became more than simple curiosity. It became something deeper.

More weeks passed, and the notes we sent changed again. We told each other secrets in simple English or badly drawn Hanzi. Secrets turned to confessions, of desires unfulfilled, of profound loneliness. We were two broken things tethered by shared emptiness. Each message we sent, each tiny piece of ourselves conveyed through the hollow space between us made me feel full for the first time in my life.

For three months, Chu Hua and I communicated through our strange connection. It was then I noticed my hole was shrinking, closing. It terrified me. I was afraid I would be cut off from her, but when I told Chu Hua about it, she said it was happening to her, too. Then we understood, and we were no longer afraid.

The last thing we passed were pictures of ourselves. Hers came first, an actual glossy photo. She was wearing a blue sundress and standing in a vast field of yellow flowers, like a single drop of rain on a golden sea. Her black hair was long, past her shoulders, and it hid part of her face, but I could see she was smiling. On the back of the photo was an address written in English.

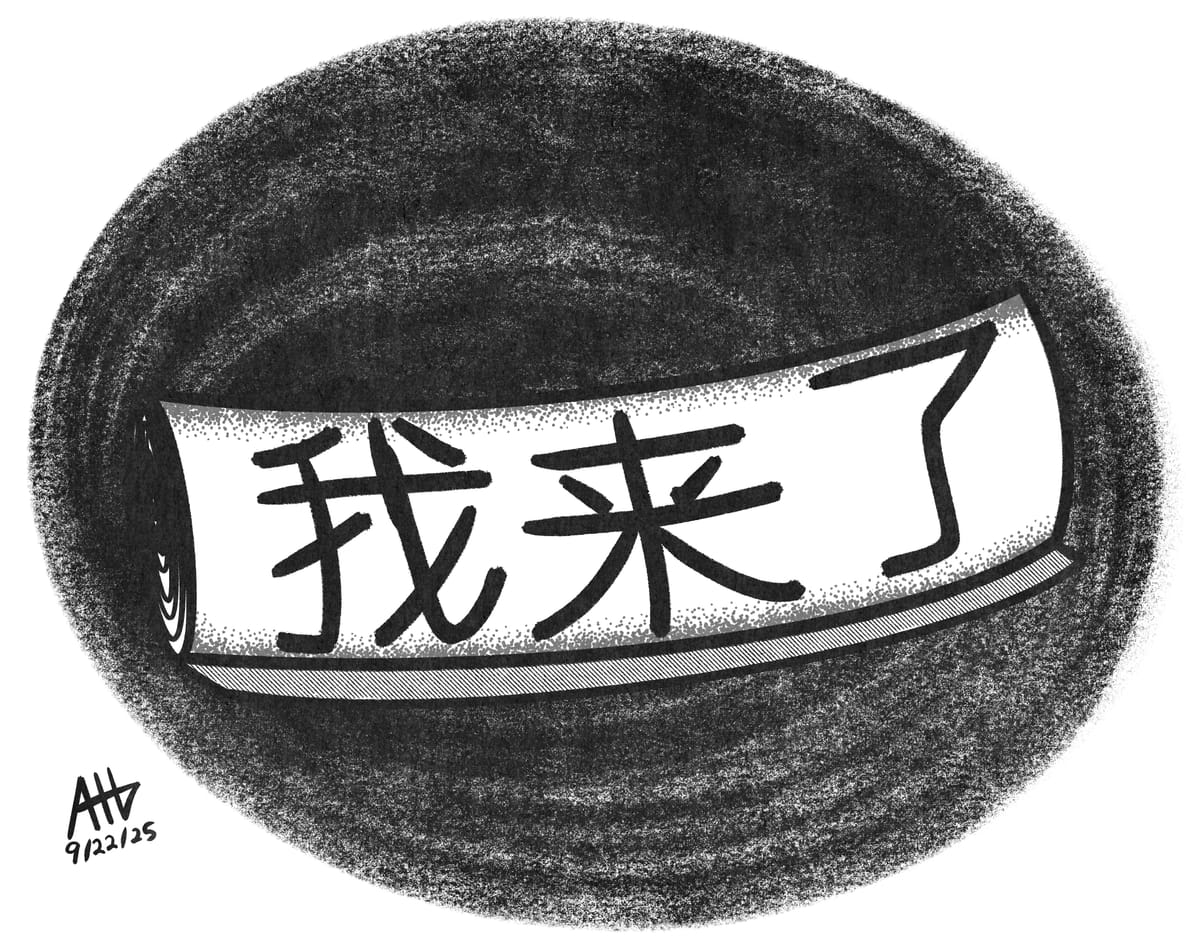

I took a selfie with my phone and printed it out. On the back of my photo, in careful Hanzi, I wrote, I’m coming. I rolled the photo into a tight scroll and pushed it through the hole, now about the size of a quarter.

I bought a one-way ticket to Kunming, China, and the hole disappeared.